8th November 2016

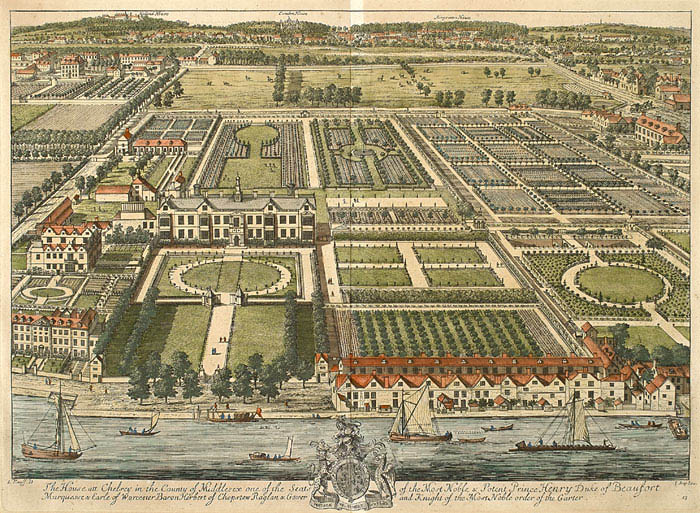

Chelsea has an unusually large number of mature mulberry trees for a London borough (around 20 at the last count). While they’re not all as old as they look, their locations reveal a rich history, ranging from Thomas More and Henry VIII in the 16th century to a short-lived silk farm and mulberry plantation 200 years later.

This old black mulberry in the communal gardens on the east side of Elm Park Gardens may date back to 1718, or at least be a descendant of an 18th century tree.

Hidden in a private communal garden between the mansion apartments of Elm Park Gardens and the houses on Old Church Street stands (or rather lies) a large, black mulberry tree, sending branches and multiple trunks upwards and sideways. It has another, albeit younger, cousin on the lawn in Elm Park Gardens itself, on the opposite side of the road. A block away, a lone black mulberry stands on the north side of Mulberry Walk. And just across the Kings Road, in the courtyard of Argyll Mansions on the corner of Beaufort Street, is another fine Morus nigra, also out of sight.

All of these trees may be related, if not genetically, then at least historically. And, unlike most of the surviving old mulberries in London, they may actually have something to do with silk…

Black mulberry in Mulberry Walk.

Chelsea Silk

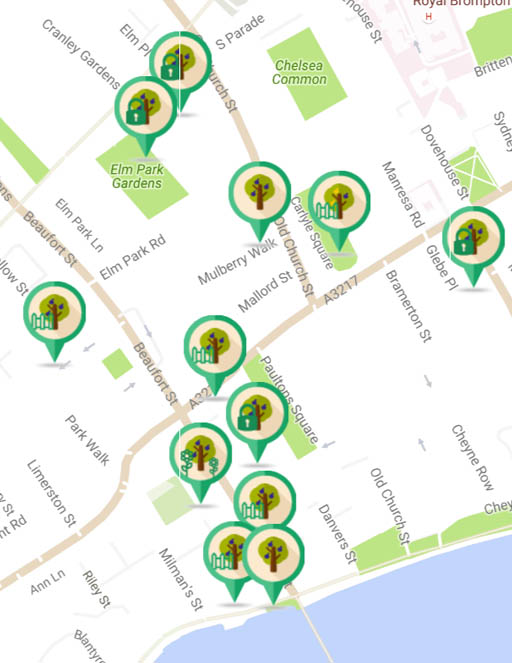

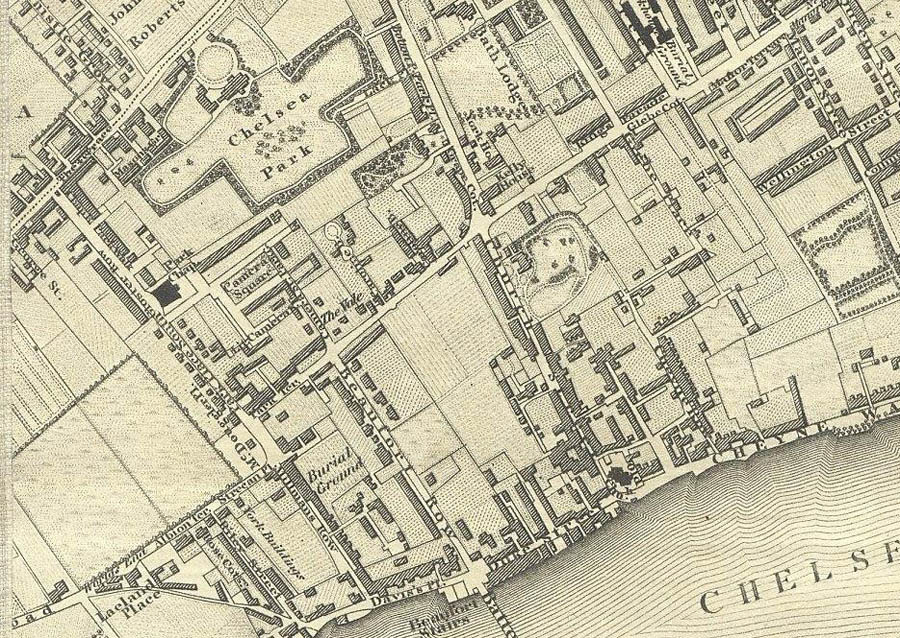

Chelsea in 1664 James Hamilton map, redrawn in 1717.

In 1524, when Thomas More bought land to build his mansion by the Thames, Chelsea was just a small village with a manor house, parish church and a few cottages. And while others followed More, including Henry VIII himself, building fine palaces set back from the Thames, the 32-acre area of More’s estate to the north of the King’s Road, known as ‘The Sand Hills’, remained arable and pasture land into the early 18th century.

So, in 1718, when John Appletree of Worcester decided to launch his Raw Silk Undertaking1, Chelsea seemed a perfect site for a mulberry plantation to feed the silkworms. It had long been used for horticulture and from 1613 exotic plants were being grown in the newly established Chelsea Physic Garden by the Thames.

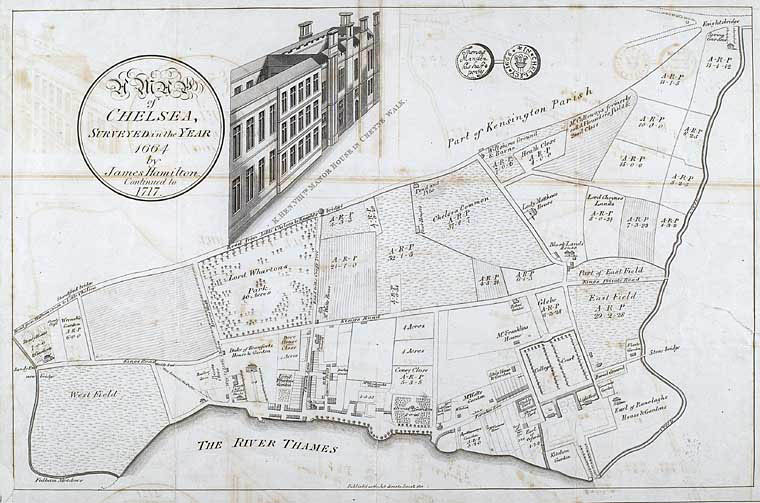

Henry Barnham, a local resident and writer on natural history, encouraged Appletree’s project and actively promoted a site by then known as Chelsea Park -- previously More’s Sand Hills -- which today corresponds to the area bounded by Fulham Road to the north, King’s Road to the south, Park Walk to the west and Old Church Street to the east. The Earl of Middlesex (Lord Treasurer Cranfield) had purchased the site in 1620 and enclosed it with a wall in 1625. In 1717 it was owned by the Marquis of Wharton and, on Hamilton’s 1664 map, which was redrawn in 1717, it is labelled as Wharton’s Park and estimated at 40 acres, suggesting it may have been extended slightly.

Kip’s view of Beaufort House, on the site of Thomas More’s estate, in 1708. Chelsea Park can be seen north of the formal gardens.

Although previous attempts to establish an English silk industry using home-produced silk had failed, the turn of the 18th century had seen a rapid expansion of English silk weaving based on expensive imported raw silk and drawing on the skills of Huguenot weavers who had settled in Spitalfields and Bethnal Green. Many thousands of Huguenots came to England to escape the religious persecution that followed the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685.

Not deterred by the failure of James I’s silk project a century before, Appletree thought that there was still a handsome profit to be made by producing the raw silk, rather than importing it. He took out patents on an ‘evaporating stove’ to keep the silkworm eggs at a constant temperature and devised a way to supply the larvae with dry mulberry leaves even if it was raining. In 1718 he was granted a 60-year lease on the site by William Sloane, nephew of Sir Hans Sloane, and planted 2,000 mulberry trees, both black and white in Chelsea Park. He also built houses to incubate the silkworm eggs, raise the larvae and harvest the cocoons. The Raw Silk Undertaking was listed on the rudimentary stock exchange of 1720 with an authorised capital of £1 million.

Short-lived success

The project seemed to flourish at first and satin garments were woven from it for Caroline of Ansbach, Princess of Wales. But by 1724 the project had already floundered and in May that year John Appletree had become bankrupt.

It is not certain what led to the dramatic failure. Ventures like this were extremely volatile, as witnessed by the collapse of the South Sea Bubble in 1720. Also, in 1721 Walpole had removed import tax on raw silk, making it hard to compete with foreign imports, especially with cheap raw silk coming from Bengal and other colonies in ‘East India’.

Goodbye Chelsea Park

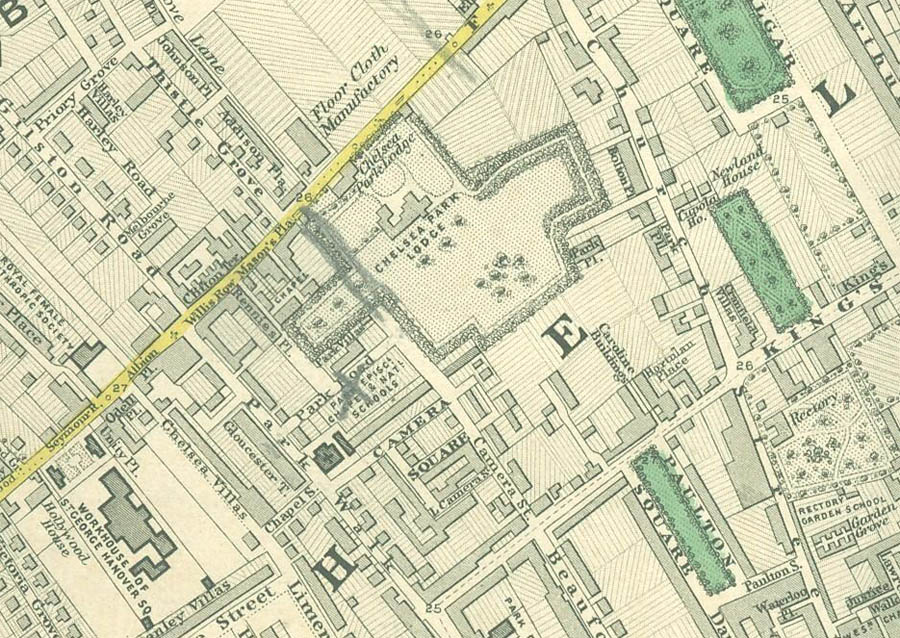

Left: Chelsea in 1746, from John Rocque’s map of London. Right: Cary’s 1799 map of Chelsea.

After Appletree’s bankruptcy, William Sloane granted a new lease to Sir Richard Manningham, who sold and grubbed out most of the mulberry trees, divided Chelsea Park into lots and sold them off. However, although the park was gradually developed over the next century, a substantial area of open space was preserved until around 1876.

Left: Chelsea Park on Greenwood’s 1827 map. Right: Chelsea in 1862, from Stanford’s map

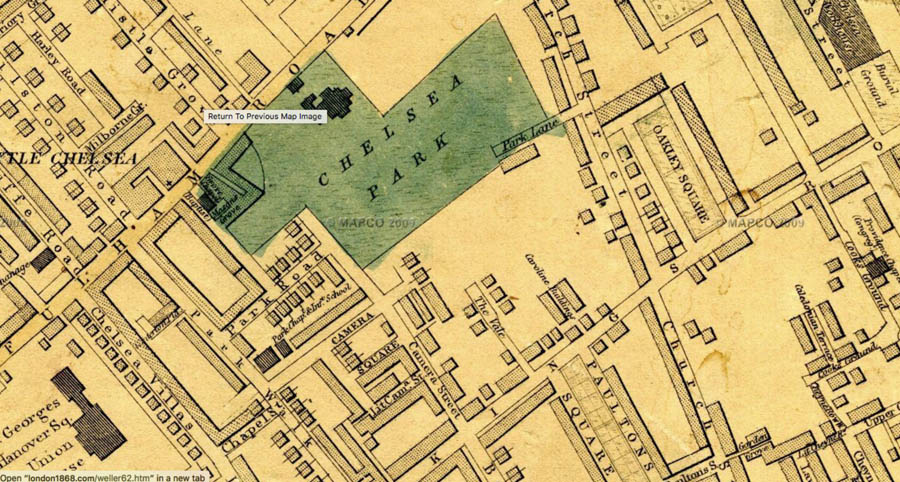

On November 24, 1875 The Times published a letter by a young medical student at St George’s Hospital, Frederic Dawtrey Drewett, protesting at plans to build on Chelsea Park. “Through its old iron gates,” he was to reminisce, nearly fifty years later, now a distinguished retired surgeon and author, “which opened onto the Fulham Road opposite […] could be seen a park of cedars, old mulberry trees, elms and whitethorn, full of blossom in the spring, all set in long grass – more like the country than any London suburb.”2

A year later, he writes, “Chelsea Park – trees and all – had disappeared, and the bricks and mortar of the ‘Elm Park estate’ were settling down upon the ‘paradise’ that had been Sir Thomas More’s.”

All that remains today are a few street names, including Chelsea Park Gardens and Mulberry walk. It seems very likely, though, that the old, recumbent mulberry in Elm Park Gardens (east side) – and perhaps some of its neighbours in nearby gardens -- has survived as a reminder of John Appletree’s original venture 300 years ago, when it was just one of 2,000 trees.

Chelsea Park in 1868 (Edward Weller map).

Food for thought

Interestingly, the white mulberries in Chelsea Park were apparently not spared – just the black ones. If not used as part of a silk industry, whether on a cottage or industrial scale, white mulberries have little interest for the horticulturalist. Their fruit is rather insipid and they do not grow into gnarled, spreading trees, like the black mulberry, which makes an exotic landscape feature. This could also explain why no white mulberries have survived from James I’s experiment in the early 1600’s. It may not have been that he only chose the “wrong” mulberries. Perhaps he planted both, but the white mulberries were all grubbed out. After all, it was well known at the time that silkworms preferred white mulberries and they had already been reported in gardens since late Elizabethan times.

Notes

1. See: Barbara Smith, An attempt to grow raw silk in Chelsea in the eighteenth century. Chelsea Society Reports (1971), 17-21.

2. Dawtrey Hewitt, The Romance of the Apothecaries’ Garden. Cambridge University Press. 1923