3rd April 2024

by Peter Coles

On an overcast day just before Easter, my mulberry-sleuthing companion, Susan Whitfield, and I braved the icy Icelandic winds to track down an old Black mulberry tree in Gunnersbury Park, West London, which had been entered on the Morus Londinium map some time ago. Neither of us had been to the park before, so it was a joy to discover its magnificent heritage trees, landscaped gardens, ponds and historic houses as a bonus.

Paper mulberry

Before getting to the Black mulberry, we spotted what turned out to be a Paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera), standing alone, south-east of the two elegant, white Grade II Listed buildings at the top of the park. These were home to the wealthy Rothschild family of bankers in the 19th century (their first country estate), until they were sold to Ealing and Acton (now Hounslow and Ealing) borough councils in 1925, along with their extensive 75 hectare (186-acre) grounds. The estate was transformed into a public park and opened by the then Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, in May 1926.

Paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera), with Gunnersbury House (right) and

Gunnersbury Park Museum (left).

In fact, the Paper mulberry is no longer classified as a mulberry (Morus) species, though it is still part of the Moraceae (mulberry and fig) family. The inside bark (bast) of the Paper mulberry, along with a medley of other fibres (like White mulberry and hemp) was used to make the first paper money in 7th century Tang dynasty China, hence its name. It is also the basis for the cloth known as tapa, still widely used in Polynesia, and the fine Washi (Japan) and Hanji (Korea) papers, prized by artists and artisans. The flowers and fruit of the Paper mulberry are unusual (nothing like the familiar mulberry) and worth looking out for later in the year.

The Black mulberry

Gunnersbury’s fine old Black mulberry (Morus nigra) is harder to find, tucked away near the foot of steps leading up through an arch to the terrace of Gunnersbury Park House (now the Museum), often referred to as the Large Mansion, to distinguish it from its neighbour, Gunnersbury House (the Small Mansion), currently being renovated.

.jpg)

The recumbent Black mulberry is dwarfed by a magnificent Cedar of Lebanon.

Probably dating from the 19th century and planted by the Rothschilds, the mulberry keeled over at some point – as they invariably do – having reached a height of about 11 metres (36 feet). Now sprawling in a ‘V’ shape in the shadow of a magnificent Cedar of Lebanon (over 200 years old) the mulberry is sending its previously horizontal branches vertically to form a new, squat crown. Left alone, it could continue to thrive like this for centuries to come, eventually looking more like a grove of mature trees than the upright, forked-trunk tree that once stood here.

The mulberry continues to thrive lying down

That said, following the almost incessant rains of February and March, the ground under the tree is sodden and waterlogged, which isn’t ideal. Beneath a surface of gravel, the soil here is London clay, which doesn’t drain well. And this (northeast) part of the park has an abundance of water anyway, with a line of springs lining Popes Lane at the top of the Park that feed ponds further down.

A young Black mulberry (right) growing near the old tree is healthy but showing signs of stress

Near the apex of the right-hand trunk of the recumbent Black mulberry is what may be a semi-mature, 15-foot scion. It seems to have no leaf buds on its lower branches, which are brittle, but the upper crown seems healthy enough. It may (ironically, given its presently saturated soil) have suffered stress in the hot, dry summers over the past few years.

A tale of two houses

Gunnersbury Park has a fascinating history spanning over 600 years. This has been described by local historians Val Bott and James Wisdom in their beautifully illustrated 2018 guide, Gunnersbury Park, so we won’t go into detail here. That said, it is a wonderful tale of love and lavish care by successive owners – with one exception, builder John Morley – to develop and embellish the grounds over a period spanning more than six centuries. Let’s have a lightning look, though.

The name Gunnersbury derives from Gunhilda, a common woman’s name in the 13th century, although the site itself has Saxon links. The estate was first granted to Edward III’s mistress, Alice Perrers, in 1373, and not long after, around 1390, passed to the Frowyk family, with whom it remained until the 1580s.

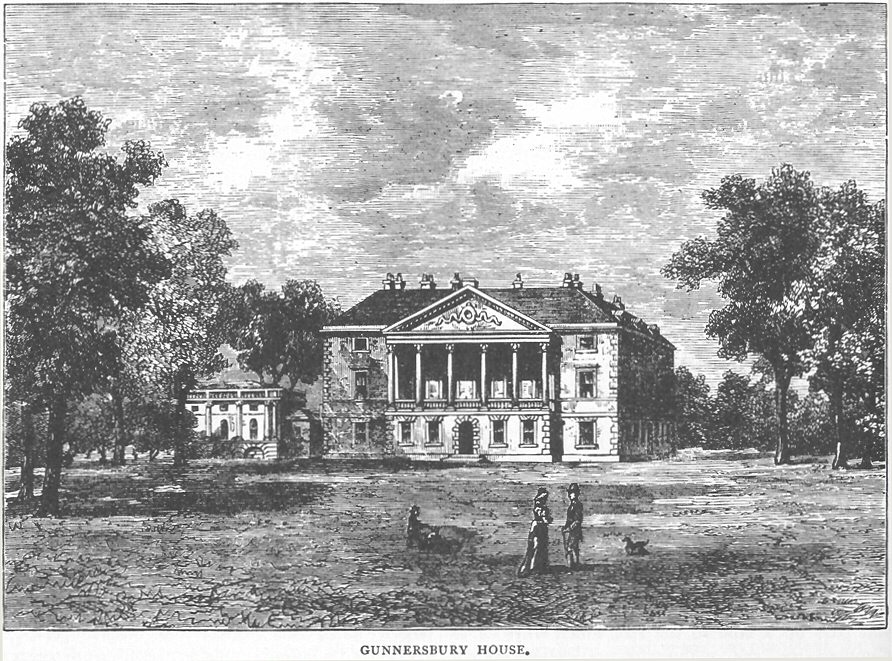

The Palladian Gunnersbury House. Engraving, 1750, [Wikimedia Commons]

It was Sir John Maynard, a wealthy lawyer and MP, however, who laid the foundations for the park we see today, acquiring the property around 1654. He constructed a fashionable Palladian mansion (where the two Regency houses now stand), enclosing and landscaping gardens within a brick wall, the remains of which can still be found in a few places (such as behind the Orangery).

When Henry Furnese purchased the Gunnersbury estate in 1739 he set about further transforming the house and grounds, employing the celebrated architect, William Kent. The Temple, Round Pond, and the older Cedar trees were all probably the inspiration of Kent. In 1762, the house and grounds passed to Princess Amelia, daughter of George II, who also lavished a fortune on her home, building a grotto and bathhouse, remains of which have survived, beyond the terrace of the Small Mansion.

In 1800, the Palladian house and grounds that Amelia had embellished were sold to what, today, we would call a property developer, John Morley. No sooner had he acquired the estate than he demolished the house and divided the grounds into 13 lots, intending to build independent villas on them and make a fortune. Fortunately, a wealthy entrepreneur, Stephen Cosser, bought Plot 1, building the Small Mansion (Gunnersbury House) and landscaping his part of the estate. The adjacent Plot 2 was bought by a building contractor, Alexander Copland, who constructed Gunnersbury Park House (the Large Mansion) and purchased some of the other plots, scuppering plans for multiple villas on the site.

In 1835, wealthy banker, Nathan Maynard Rothschild and his wife Hannah bought the Small Mansion, gradually adding land to the west and putting their indelible mark on the house and grounds. On the death of Nathan just a year later and of Hannah in 1850, the house passed to their eldest son Lionel. In 1889 their own son, Leopold (Nathan and Hannah's grandson), was able to buy the neighbouring Gunnersbury House (Small Mansion) and finally reunite the divided estate.

The Park’s heritage trees

One of two surviving 17th-century Yews by what was once the Horseshoe Pond

With a landscape garden history spanning almost four centuries, dating the stunning heritage trees in the park is not easy. Fortunately, in 2014, a team from the University of East Anglia (UEA) published the results of their Heritage Tree Survey of all the park’s trees. A year earlier, archaeologists from the Museum of London published their Historic Environment Assessment in 2013, complementing their findings.

According to the UEA study’s authors:

“Little survives of the seventeenth and eighteenth-century planting within the park - some yews, a few cedars, a couple of beech, two possible examples of sweet chestnut and perhaps three or four oaks. […] Gunnersbury is thus essentially a nineteenth-century landscape, although the Rothschilds continued to add to the planting through the first quarter of the twentieth century.”

Our Black mulberry, then, most likely dates from the Rothschilds' time, anywhere between 1835 and 1925. Its dimensions (a single-stem equivalent girth for the two trunks of 184 cm and a recumbent trunk length of 11 metres) support the idea that it was planted around the mid- or late 19th century. Nathan and Hannah received advice from the celebrated garden designer, John Claudius Loudon (1783-1843), whose publication, The Villa Gardener (1850) recommended planting a Black mulberry as one of the first trees in the gardens of the villas that were beginning to mark the expansion of London’s suburbs.

The Museum

The Museum (closed Mondays) in the Large Mansion is definitely worth a visit. Although now unfurnished, its lofty, empty rooms, complete with fireplaces, chandeliers and wide views, let the imagination roam. Indeed, footballer Eric Cantona and Noel Gallagher, lead singer of the band Oasis, used the house as a setting for a rather cheesy video, which nevertheless has the merit of showing the rooms furnished, in luxurious splendour.

Photos © Peter Coles